Ceramics Week

7 December 2008

By Scott Sorset

Colleen Reese and Jake Shidner working on reconstructing their broken ceramics to their former glory.

Ceramics are some of the most commonly found artifacts from underwater sites. These artifacts are generally very durable compared to other artifacts such as wood or rope. However, and yet in order to survive life on land, they still need conservation. This is where the mad science of conservation is able to recover lost detail, protect the object, and even reconstruct entire pots from their fragmentary states.

Ceramics represent the everyday lives of everyday people. Understanding the designs on the plates can help archaeologists understand what was popular, when it was popular. Ceramics can even tell us who made the pots. In addition, studying the shapes, designs, rims, and bases can create a timeline of ceramics that reconstructs elements of life in the past. If archaeologists were able to see the dinner plates from your house, they could evaluate your plates to those of your neighbors. From those comparisons, things like wealth and status are evaluated to make statements about you and your life.

The students and professors at the University of West Florida have recently recovered ceramics from the Emanuel Point II shipwreck as well as from historic shipping wharves in Pensacola Bay. After these objects are recovered from the field, they are transported to the conservation laboratory at UWF. The objects are transported in water and kept wet at all times. During transport, every effort is made to ensure that no harm comes to the objects and ensure that they remain in the same water from which they came. This helps to make sure that no harm comes to the artifact. Once the artifacts arrive in the laboratory, they are placed into fresh water to remove the years of buildup of salt from within the ceramics. If the salts are not removed the artifacts could be damaged, or even worse, destroyed. This is because when it comes time to dry the objects, the removal of the salts will prevent the beautiful glazes and designs from being destroyed by the formation of salt crystals.

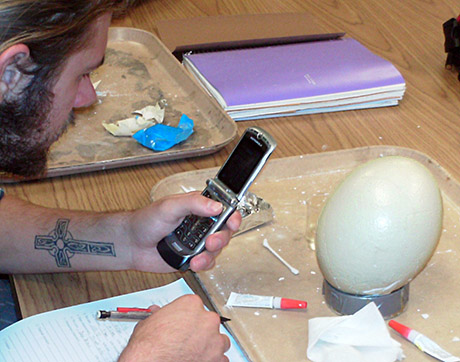

Brian Durnan celebrating after restoring his Ostrich Egg.

After desalinations is complete the conservators evaluate each and every object, recording every detail and photographing them before the conservation process really begins. Numbers are assigned, databases updated, and further research begun all in an effort to understand more completely the site from which they came.

Almost all of the ceramics that enter the laboratory have some organic staining which must be removed in order to inspect and record the decorations. After 450 years on the bottom of Pensacola Bay these stains form from a variety of sources. Usually it looks dark black with makes it impossible to see any detail from the ceramic. However, these stains can easily be removed using baths or spot treatments of hydrogen peroxide. Other ceramics contain iron staining which is removed using another chemical known as disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid or EDTA. Often times applications of these chemicals is done using gentle swipes with Q-tips. Extreme care is taken to prevent damage to the artifact, since these treatments are either corrosive or acidic. Extreme care is taken at all times to protect conservators from exposure to these chemicals.

The goal of the conservation of ceramics is an artifact that will remain for all time in the state in which it was found or better. This is accomplished through hard work and determination. Allowing students to work on these artifacts is an honor and requires a faculty with patience and trust. The conservation class of 2008, however, has proven they are more than worthy and has exceeded expectations in almost every regard. Be sure to stay tuned for the next conservation blog on the conservation of organics like rope.

Please feel free to contact us if you have any questions or concerns at: mua@keimaps.com.

Return to Project Journal home page.