The Lake Ontario Maritime Cultural

Landscape Project

27 July 2007

By Ben Ford

This journal entry pitches our story forward approximately eight months. In the last entry, I was wandering the shores of Lake Ontario looking for promising areas to survey, and now, suddenly, we are ready to start the fieldwork. What happened in between? The academic year. The Lake Ontario Maritime Cultural Landscape Project, however, did not grind to a halt while I was busy poisoning undergraduate minds with talk of culture and taking classes about the human impact on the environment. Rather, I was busy looking for funding, organizing equipment, arranging for a boat, finding an engine to power the boat, learning software, and hundreds of other necessary, occasionally painful, and generally uninteresting tasks. There is an old adage that for every hour of field work you can expect to spend three to ten hours in the laboratory or library. I’d like to add at least an extra hour of logistics to that equation.

Perhaps why terrestrial archaeologists are not invited on underwater projects. (large view)

Yet, it was all worth it. We are now ready to survey. You may have noticed the change in number; this is no longer a one-archaeologist show. Throughout the 2007 fieldwork, I will be assisted by fellow Texas A&M graduate student Jessi Halligan, local volunteer Terry Baker, and a host of other friends (please see the acknowledgments for a full list). And what will all of these people be looking for? Pretty much anything that shows evidence of human presence from approximately 5000 years ago, the time that Lake Ontario levels stabilized, through AD 1900. These sites can include projectile points, lithic scatters, fish weirs, and evidence of portage routes or canoe tips, as well as landing places, docks, wharves, shipyards, shipwrecks, mills, evidence of stone hooking, and habitation sites of all periods. The list goes on, but that gives you a flavor of the breadth of our interests.

Heading out for the day, team member Jessi Halligan prepares for the survey while William Burdick pilots the boat. The magnetometer can be seen strapped to the starboard pontoon and the side-scan sonar on the port. Both computers are housed in cabinet sitting amidships. Photo by Norm Johnston, Watertown Daily Times. (large view)

We begin our work with the offshore remote sensing survey, because, frankly, it scares me the most. The offshore survey is the most weather dependent (anything more than a 10 mph wind and we can not hold a survey line or control the computer cursor), involves the most logistics, and requires the most equipment. We are surveying with a Geometrics G-882 magnetometer linked to a Panasonic ToughBook running Hypack software and a Marine Sonic 600 kHz side-scan sonar controlled by SeaScan PC software on a Marine Sonics customized desktop computer. Both computers receive differentially corrected position data from a Trimble DSM-232 global positioning system (GPS). All of this means that we have nice toys that require constant attention to detail. Add the wrinkle of powering all of the equipment with car batteries in a well-used 18-foot inflatable boat and you can see the potential for adventure. As a result, we spent our first week in New York setting up the equipment on dry land, calibrating it, making sure all of the pieces talked to each other, getting the boat in the water, and running practice lines.

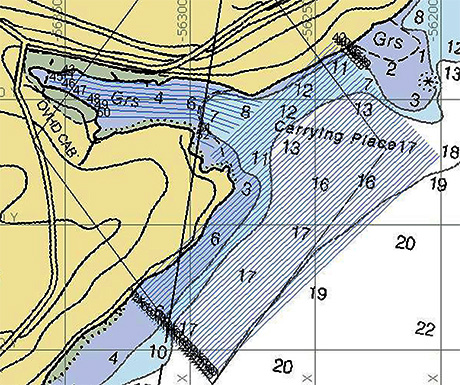

After seven days in the area we finally felt ready to tackle a real survey. With the magnetometer trailing five meters (16.5 feet) off the starboard quarter (so that the metal of the boat and engine do not interfere with its operation) and the side-scan 1.5 meters (5 feet) below the port side, and both computers in our “custom cabinet” (take a look at the photographs) we started work at Long Carrying Place. This location (number two on last entry’s map) is a known portage route and an attractive inlet now lined with cottages. It took us a bit to begin following even remotely straight survey lines (working-class kids from land-locked states are not natural boat pilots). Straight survey lines are important because they guarantee that we cover the entire area. Eventually, we learned to watch the Hypack navigation bar until we were lined up and then pick a point on the horizon for reference using the corner of our cabinet as a sight.

We surveyed at Long Carry Place for three days and recorded approximately 80 targets. Many of these targets are likely natural (rocks and weeds), modern, or nothing at all, but we will dive on them to find out. We encountered a number of problems, including weeds and water depth. Both the magnetometer and sonar towfish are designed to travel well below the water's surface; however, we are working in very shallow water and really don't want to plow a trench through the bottom. We solved this problem by lashing inner tubes to the magnetometer and pulling the side-scan close beneath the boat. However, much of the side-scan data is still hard to interpret due to the shallow water and weeds. Sonar sends out an acoustic signal that reflects off objects and produces a picture of the lake floor. However, in shallow water the angle of the signal is so low that any object close to the sonar produces such a long shadow that everything behind it is invisible. The large number of weeds has a similar effect, obscuring objects and making their shapes hard to decipher. July and August are not the best months for a nearshore survey, but due to equipment schedules this is the time we have, and we'll make the best of it. The weeds also played havoc with our motor, wrapping themselves around the prop and making us afraid of losing our only means of transportation. At one point we paddled the inflatable up into the head of Long Carrying Place with the magnetometer floating behind us like a slow-moving shark to see if we could get any hits (we did).

Chart of Long Carrying Place showing planned marine remote sensing survey lines spaced 15 meters (49 feet) apart. (large view)

The weeds will continue to be a problem, but I think we can still collect usable data. We will dive on our targets in coming weeks, but first we will survey Wilson Bay (number one on the map) and, this weekend, begin conducting interviews with property owners. All of these aspects of the survey will be covered in future entries.

Further Reading:

Breiner, Sheldon

....1999 Applications Manual for Portable Magnetometers. Geometrics, San Jose, CA. Available at: ftp://geom.geometrics.com/pub/mag/Literature/m-ampm-05Apr06.pdf

Breiner, Sheldon

....N.D. Marine Magnetics Search. Geometrics, San Jose, CA. Available at: ftp://geom.geometrics.com/pub/mag/Literature/MM-TR1.pdf

Fish, John P. and H. Arnold Carr

....1990 Sound Underwater Images: A Guide to the Generation and Interpretation of Side Scan Sonar Data. Lower Cape Publishing, Orleans, MA.

Fish, John P. and H. Arnold Carr

....2001 Sound Reflections: Advanced Applications of Side Scan Sonar. Lower Cape Publishing, Orleans, MA.

Please feel free to contact Ben at ben.ford@iup.edu with any comments, questions, or suggestions during the weeks to come.

Return to Project Journal home page.