History

27 June 2007

By Michelle Damian

I’m embarrassed to start this entry out the same way as the last one – so much for my good intentions of updating more frequently. Once again other things had to take priority; another university field project occupied me the past month. I love the fieldwork, but muddy North Carolina rivers are a far cry from Japanese woodblock prints, so it wasn’t quite directly related to the thesis project!

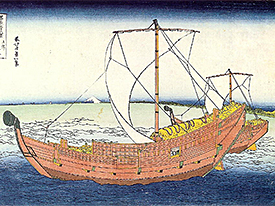

"At Sea off Kazusa" by Hokusai, from Hokusai (Gian Carlo Calza), shows two bezaisen, large merchant vessels. (large view)

I did squeeze in some thesis work over the past month, mostly devoted to writing the historical background necessary to place the scenes depicted in the woodblock prints into context. The major challenge here was to compress approximately two hundred years of Japanese history into fifteen pages or so. In talking with one of the professors on my thesis committee, I mentioned that it’s been a fine line to walk as I tried to adequately introduce the various aspects of society and government that are important to understanding both maritime practices and the woodblock prints, yet not succumb to the temptation to write pages and pages about only tangentially related topics. He reminded me that as a Western maritime archaeologist, he’s not that familiar with Japanese history, so I needed to ensure that I gave enough of a comprehensive background. That means that a Japanese historian may read what I have written and wonder at the amount of time I devote to “well-known” topics, such as the Tokugawa (Edo) period class system of samurai, peasants, merchants, and artisans. The average Western maritime archaeologist reading my thesis, however, is unlikely to have had much exposure to Japanese history, simply because little work has been published in English on the topic. Since the audience determines the manner in which I must introduce the topics, I have tried to strike a balance with this draft. I’ll soon turn it in to the head of my thesis committee – we’ll see what he says about it.

"Sketch of Tago Bay near Eijiri on Tokaido" by Hokusai, from Hokusai (Gian Carlo Calza) shows fishermen casting their nets. (large view)

So little has been written (in English especially) about Japanese maritime history that writing this chapter has been a process of pulling together bits and pieces from any number of works. It has been a matter of finding mention of watercraft even in seemingly totally non-maritime-related books – for example, Cecelia Segawa Seigle’s Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan had a description of a visitor navigating the waterways on a visit to the pleasure quarters. Memoirs from the handful of foreigners that lived in Japan during the Edo period have been helpful, as they talk about the various watercraft they encountered in their limited travels around the country.

Some of the Japanese-language sources that I have access to show the great variety of boats that existed. Adachi Hiroyuki’s Nihon no Fune (Japanese Boats) mentions a government-produced contemporary scroll named the Funakagami, created in 1802, specifying the different types of boats used on the rivers near Edo. A picture of the boat alongside its name and general dimensions were recorded for the local river officials to use for taxation purposes.

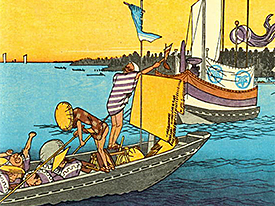

"Arai" by Hiroshige, from "Thirty-Six Views on Mount Fuji" depicts a daimyo's ferry crossing the waterway. One of the foreign residents in Japan described in his memoirs a similar procession at Arai. (large view)

A reproduction of parts of the Funakagami at the Museum of Maritime Science in Tokyo shows boats ranging from takasebune (a shallow draft cargo boat) and similar transport vessels to chabune, “tea boats,” and even yubune, “bath boats” used as floating washroom vessels for fishermen wanting to clean off after a long period at sea, or men and women needing to freshen up after time in the pleasure districts. All of this research has both shed light on some of the things I’ve seen in the woodblock prints and has revealed more information that had not been recorded in the prints alone.

"Actor Prints" by Kunisada, from A Treasury of Japanese Woodblock Prints: Ukiyo-e (ed. Kikuchi) depicts three Kabuki actors posing on a boat. (large view)

The next step involves more historical research about the culture of woodblock prints in an effort to understand why the artists chose to depict the scenes they did. I’ll work on that next while waiting for the comments and revisions on this first chapter.

As always please feel free to contact me at muaprojectjournal@yahoo.com with any comments, questions, or suggestions during the weeks to come. Yoroshiku onegai shimasu ("I look forward to your good favor").

Return to Project Journal home page.