Returning

4 June 2008

By Michelle Damian

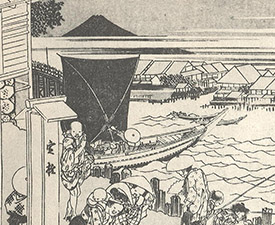

Print of three women on a boat by Utamaro. Note the gauzy robe that one woman is peering through. Print from Ukiyoe, Images of an Unknown Japan, British Museum Publications. (large view)

I ended my last entry saying that I would continue to squeeze in thesis writing during my first-year PhD coursework. While not much writing actually happened since September, the past two semesters have exposed me to a wide variety of scholarship on Japanese history and material culture that has helped provide a better context for much of the thesis research. I’ve also been fortunate to be able to present the preliminary results of this project at the Society for the History of Technology (SHOT) and the Society for Historical Archaeology (SHA) annual conferences. The latter was particularly exciting, as it was part of SHA’s first-ever symposium on Asian seafaring.

After spring semester ended I gave myself a couple days off, and now have plunged back into thesis writing (which I’m sure my committee will be pleased to hear). I had had a draft of the “general history chapter” written, and first went back to edit that. The next chapter I turned to dovetails with the as-yet-unwritten methodology chapter. As an introduction to my data set, and in order to assess the reliability of using woodblock prints as valid evidence, I needed to discuss the background of woodblock print production and publishing. It’s great that I have over two hundred prints with ships in them, but if there were outside influences that skewed the production of such prints or the accuracy of the scenes represented, I needed to find out about it.

Early woodblock prints were mostly "beautiful women" pictures, erotic prints, or images of Kabuki actors. These relatively flashy scenes were the advertisements of their day, promoting certain courtesans or actors, and lent themselves well to the mass-production afforded by woodblock prints. Those individuals' changing fashions could be reflected quickly in new prints. The Kyoho Reforms (Kyoho era: 1716-1736), however, saw edicts promulgated that restricted publishers' production of "immoral" or "excessively luxurious" prints.1 This certainly facilitated the growth of both "everyday life" prints of townspeople or travel scenes, as well as of landscape prints in general. Not only did these conform to the new edicts, they were also not subject to the changing whims of the fashion world. Mount Fuji continued to tower over the horizon no matter what costume the latest popular actor wore. As publishers' investments in the creation of the woodblocks for a single print were substantial, the ability to reuse the materials necessary for landscape prints was not unappreciated.

Detail of a fisherman pulling back a net from Fuji in the Evening Sun at Shimadagahana, by Katsushika Hokusai. From Hokusai, One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji by Henry D. Smith. (large view)

Artistic techniques also evolved during this era. Black-and white prints gave way to the multicolored nishiki-e, which also allowed artists to create an apparent layering of materials. This is particularly relevant to the study of maritime prints in examining fishing techniques and nets, as I talked about in the “Time” entry. Is the prevalence of nets in these scenes an accurate reflection of the most common fishing tool, or is it simply a way for the artist to demonstrate his ability to manipulate the woodblocks? It is impossible to know only from the woodblock prints. I have also become wary of artistic copying. Artistic schools produced manuals that detailed the techniques characteristic of each school, and artists would pay homage to their mentors by using their figures.2 There are many instances of artists copying themselves as well. A single fisherman pulling back on his yotsude-ami appears in almost identical form in at least two different Hokusai prints. The demand to create aesthetically pleasing images quickly may have enticed artists to reuse tried and true components of other pictures. While I do believe there is a high degree of accuracy in these prints, these and other factors emphasize the need to look beyond only the prints themselves to understand Edo-period Japanese maritime culture.

Fisherman casting his yotsude-ami, Tone River in Shimosa Province, by Katsushika Hokusai. From Hokusai by Gian Carlo Calza. Click on the image to zoom in for a closer look.

The next step is to create a “catalogue” of the prints that I have, typing up brief descriptions of the maritime features of each scene. This will not only get me reacquainted with the prints that have been sitting in folders while I’ve been in classes the past two semesters, but will also form the foundation for the larger analysis to come. My summer’s work is cut out for me!

As always please feel free to contact me at muaprojectjournal@yahoo.com with any comments, questions, or suggestions during the weeks to come. Yoroshiku onegai shimasu ("I look forward to your good favor").

________________

1Christina Guth Art of Edo Japan: The Artist and the City 1615 – 1868. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.) 1996:102.

2Ellis Tinios “Borrowed Landscapes: The Exploitation of Maruyama Shijō Book Illustrations by Ukiyo-e Artists.” In The Commercial and Cultural Climate of Japanese Printmaking, Amy Reigle Newland, editor. (Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing) 2004:166.

Return to Project Journal home page.