Advertisement in a Portland, Maine trade journal from 1894 for the sale of coal. See full ad (courtesy of Deborah Marx).

Beginning in the earliest days of New England's European inhabitation and continuing to the present, storm, fire, and collision have sent many ships to the bottom of Massachusetts Bay. These lost vessels range from small fishing boats to large steamships. Of the hundreds of ships lost over the preceding centuries, one vessel variety is particularly well represented on Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary's seafloor: the coal schooner. During the nineteenth and twentieth century's, hundreds of coal schooners loaded cargos in Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania ports and then headed north with the fuel for New England's cities and factories.

A schooner loading coal at the Norfolk and Western Railway coal pier in Norfolk, VA. Large view (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

By the start of the American Civil War, water power and wood could not keep up with the energy needs of industrialization and urbanization; coal was clearly the fuel of the future. The capital investment in manufacturing as a result of the war increased the need for the bulk transport of coal to fuel the war industries. Following the Civil War, demand continued to rise with further industrial development, the expansion of railroads, increased use of electrical power plants, and the continued influx of people into the Northeast's cities.

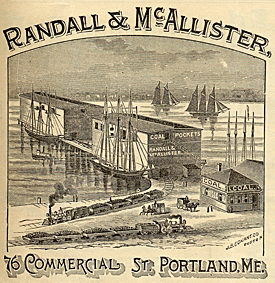

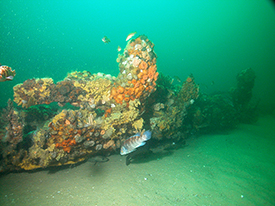

Numerous coal schooners' shipwrecks have been found in NOAA's Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary off Massachusetts (courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS). (Large View ).

The schooner, sprouting between 2 and 6 masts, was the vessel of choice for coal transport in the Atlantic coasting trade from 1860s through the 1920s. The schooner was well adapted to coastal routes with its ability to operate with a small crew, sail closer to the wind, access tight harbors, and carry large amounts of bulk material. Vessel design culminated in the great New England coal schooners that proved to be the most economical means of transporting coal to New England's cities, until competition with towed barges and steam colliers closed the last chapter on coastwise shipment of coal by sail.

This slideshow presents images of the Frank A. Palmerand the Louise B. Crary which collided collided more than a century ago.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary encompasses 842 square miles of seafloor at the mouth of Massachusetts Bay. Spanning the waters from Cape Ann to Cape Cod, the sanctuary sits astride the oceanic gateway to Boston, the destination for most of the coal shipped north. Lying on the sanctuary's seafloor, preserved by the cold and dark water, are representative examples of both the largest and smallest schooners engaged in the coal trade. To date, maritime archaeologists have located and investigated eight vessels with cargoes of coal.

5-masted schooner Paul Palmer sliding down its ways on launching day in Waldoboro, ME (courtesy of Maine Maritime Museum). (Large View ).

While the identities of most of the sunken vessels are still unknown, archaeologists have positively identified several schooner shipwrecks and uncovered their history to better understand the sanctuary's past maritime landscape. The remains of the schooner Paul Palmer and collided coal schooners Frank A. Palmer and Louise B. Crary have been the subject of recent archaeological projects and are both listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

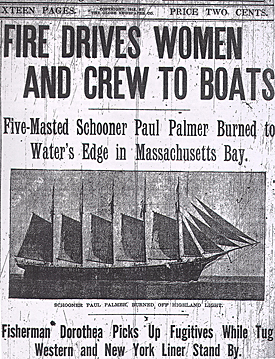

Newspaper headline reporting the sinking of the unlucky Paul Palmer (16 June 1913 Boston Globe). (Large View )

One of the sanctuary’s most amazing archaeological sites represents the final moments of the 4-masted schooner Frank A. Palmer and 5-masted schooner Louise B. Crary. The two schooners sit upright on the seafloor off Gloucester, MA in deep water, connected at their bows where they collided more than a century ago. Both hulls are largely intact from their keels to main decks with coal-filled holds and remnants from the captain’s cabin still in-place.

On a cold December night in 1902, the schooners were crossing Massachusetts Bay in tandem with three thousand tons of coal apiece for delivery in Boston. Misjudging the proximity of the Frank A. Palmer, the Louise B. Crary's first mate altered direction, putting the schooners onto a collision course that was realized too late. The crash opened large holes in both schooners causing them to sink very rapidly; both crews hurried to their longboats, but only fifteen of the twenty-one sailors made it into the Frank A. Palmer's boat. Lacking food, water, or warm clothing, the survivors floated south from the crash site out around Cape Cod enduring terrible privation. Five more sailors perished before being rescued three days later by a fishing schooner. This disaster exemplifies the hardships and danger faced by mariners carrying the fuel of the Industrial Revolution.

The Paul Palmer's frames protrude out of the sandy seafloor of Stellwagen Bank (courtesy of Matthew Lawrence, NOAA/SBNMS). (Large View ).

In shallower water off Provincetown, MA lies the remains of the 5-masted coal schooner Paul Palmer. It departed Rockport, Maine on Friday, 13 June 1913 and headed south to pick up another load of coal. Off Massachusetts on 15 June 1913, the vessel's forecastle caught fire. Unable to quench the blaze with the Palmer's own pumps and the assistance of a tug, the crew abandoned ship and were picked up by a waiting fishing schooner. Shortly thereafter, the Paul Palmer burned to its waterline and sank. The partially buried remains of the Paul Palmer lie on a flat sandy bottom with portions of the schooner's wooden hull protruding from the seafloor. At the schooner's bow is a large steam powered windlass used to raise its anchors.

The Mystery Collier is filled up to its main deck beams with coal (courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS and NURTEC). (Large View )

Not all of the coal arrived in New England packed in the hulls of large 4 or 5-masted schooners. Many smaller vessels, like the one known as the "Mystery Collier," have been investigated in the sanctuary with varying degrees of site preservation. Utilizing remotely operated vehicles, archaeologists have surveyed these unidentified sites to record diagnostic hull construction features and artifacts. These clues will help researchers narrow down the time period in which the vessel operated and shed light on the activities of these far more numerous vessels and their crews.

All that is left of some Stellwagen Bank Sanctuary shipwrecks is a pile of coal on the seafloor (courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS and NURTEC).

Impacts from commercial fishing activities have negatively affected nearly all sanctuary shipwrecks and greatly contributed to site deterioration on some sites. Large trawl nets that are towed across the seafloor collide with fragile historic shipwrecks damaging or destroying their hulls and smaller cultural artifacts. The larger coal schooner shipwrecks have withstood some of the effects of fishing activities; however, these vessels are now draped in fishing nets and line. Unfortunately, the smaller vessels are much more susceptible to damage. Several sites suspected to have been 2-masted schooners are now simply piles of coal capping lower hull structure evidenced by a few frame ends protruding from the sediment. Even durable iron fittings, such as rigging and anchors, are missing from these sites, long since scooped up by trawlnets and now decorating the front yards of Massachusetts homes.

Coal Schooner Shipwrecks in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

NOAA archaeologists are continuing their efforts to locate and document the remains of the New England coal trade through annual side scan sonar and ROV surveys in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. Shipwrecks are nonrenewable gateways to the past and it is through the interpretation of these archaeological resources that the sanctuary hopes to increase public enjoyment and appreciation of New England's maritime history and foster stewardship of America's maritime legacy.

For more information visit:

Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary http://stellwagen.noaa.gov

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov

About the Author: Deborah Marx is a maritime archaeologist with NOAA's Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in Scituate, MA. She is a graduate of East Carolina University's Program in Maritime Studies.

Comments, suggestions, and questions can be directed to Deborah.Marx@noaa.gov

Return to In The Field home page.

Comments, suggestions, or questions can be directed to research@themua.org