Commodore Joshua Barney.

Introduction

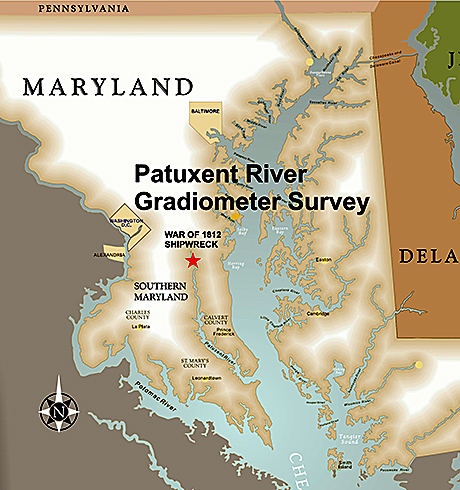

In 2010, the Maryland Maritime Archaeology Program (MMAP) of the Maryland Historical Trust/SHPO received a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (NOAA OER) to employ a multi-sensor gradiometer to search for the Revolutionary War-era State Navy vessels Cato and Hawk off Cedar Point in Maryland waters of the Chesapeake Bay. For a number of reasons, which will be discussed under Methodology, it became necessary to change the locus to the upper Patuxent River, where MMAP is a partner with the U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command and the Maryland State Highway Administration on the Search for the U.S.S. Scorpion project. The latter involves the relocation and investigation of vessel remains discovered in 1979 and believed to be those of Commodore Joshua Barney’s flagship, Scorpion, scuttled in August 1814 to prevent its capture by the pursuing British.

Background History

Although the War of 1812 was declared June 18, 1812, the British Royal Navy did not begin its blockade of the Chesapeake until December 26 and did not enter the Bay proper until February 4, 1813. With most of the regular U.S. Army on the Canadian border and presuming that the important commercial port of Baltimore was the intended target, Washington was only lightly defended. On July 4, 1813, Joshua Barney, a hero of the previous Revolution, came out of retirement to offer a plan for the defense of the Bay to the Secretary of the Navy. Barney’s proposal to constitute a fleet of fast, shallow-drafted vessels that could be propelled by oars or sail was accepted and the U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla was formed with Barney as commodore.

Map of Patuxent River Gradiometer Survey.

When Barney left Baltimore on May 24, 1814 his flotilla consisted of gunboats nos. 137 and 138, thirteen barges, a lookout boat, the row galley Vigilant, and his flagship, the modified and renamed gunboat no. 59, Scorpion, as well as a number of merchant vessels that were sheltering with the Flotilla in an effort to run the blockade. The Flotilla’s mission was to attack the British base on Tangier Island. On June 1, the southbound Flotilla came upon a portion of the British fleet in the vicinity of the Potomac River and was forced to fall back. Off the mouth of the Patuxent River, a skirmish took place, which became known as the Battle of Cedar Point. Barney retreated into the river and when pursued by the British he continued up the river and into the shelter of St. Leonard Creek. Two engagements occurred here; the First Battle of St. Leonard Creek took place between June 8-10 and the Second Battle of St. Leonard Creek on June 26. The former was fought between the Flotilla and the smaller vessels of the British fleet, as the larger ships could not manage the shoals. It ended with the British withdrawing and resorting to raiding up and down the river in an effort to draw Barney out. The second battle was engaged when Barney received orders to break out and move the Flotilla upriver in order to send his men to Washington, which was now fearful of a pincer attack since there were British forces in both the Potomac and the Patuxent Rivers. He succeeded in doing this through the nocturnal erection of a gun battery overlooking the mouth of the creek and during a predawn attack forced back the British ships sufficiently to permit the Flotilla to slip past and up the Patuxent. Prior to this action, Barney scuttled the two gunboats in St. Leonard Creek as they had previously proven impediments during the Battle of Cedar Point.

On July 27, William Jones, the Secretary of the Navy instructed Barney to ascend the river as far as possible and to have the barges hauled overland to the South River. Joshua sent his son, Major William Barney, with a few boats to reconnoiter the situation. He worked the vessels as high as Queen Anne’s town and deemed it possible but was doubtful as to how practical it might be. Subsequent instructions vetoed this and on August 21, Barney landed the majority of his men who ultimately joined the American forces that were gathering at the Washington Navy Yard and fought in the Battle of Bladensburg. The 103 men left with the Flotilla, under Lt. Solomon Frazier, had orders to scuttle the Flotilla rather than permit it to be captured by the British. These orders were implemented in the morning of August 22, 1814.

There is general consensus that Barney sailed with 18 vessels, however, he scuttled two of these in St. Leonard’s Creek in June leaving 16 to move up the Patuxent. However, Admiral George Cockburn’s description of the scuttling in the upper Patuxent notes that there were 17 vessels, of which 16 were destroyed and one was captured. As he also refers to an additional 13 merchant vessels being present, it is unlikely he would have mistaken a merchant vessel for a military one. This places up to 30 vessels in a very small stretch of river, even allowing that it may have been broader and deeper and possibly in a variation of its present configuration.

The reasons one does not virtually trip over shipwrecks include, the British capture of the merchant vessels, the almost immediate looting and scavenging by locals of the military remains as well as intensive formal salvage efforts within weeks of the scuttling. Vestiges of the wrecks remained visible into the 20th century. The Epilogue of Shomette’s Flotilla (2009) details the contemporary salvage efforts and subsequent predations on the remains of the vessels.

Additional Reading

Eshelman, R. 2005. Maryland’s Largest Naval Engagement, the Battles of St. Leonard

Creek, 1814, Calvert County, Maryland. Jefferson Patterson Park & Museum, Studies in Archaeology No. 3.

Pitch, A. 1998. The Burning of Washington, the British Invasion of 1814. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis.

Shomette, D. 1995. Tidewater Time Capsule, History Beneath the Patuxent. Tidewater Publishers, Centreville, MD.

2009. Flotilla, the Patuxent Naval Campaign in the War of 1812. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Comments, suggestions, and questions can be directed to Dr. Susan Langley

Return to In The Field home page.