Reconstruction of houses in the village of Walraversijd, Belgium. Photo courtesy of the author.

This post provides a brief introduction to current projects in European underwater archaeology or 'underwater cultural heritage' as it is called by world heritage organizations. This topic was a part of my postgraduate thesis project under the title of "Conservation and Presentation of Underwater Cultural Heritage to the Public; case study: Current projects in Belgium" in 2008 at Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium. Although underwater archaeology is a relatively new area of Cultural Heritage, it is increasingly seen as a crucial and remarkable part of the human heritage.

The legal discussion about underwater cultural heritage and maritime archaeology started in Europe about mid 20th century although underwater excavation and exploration began long before then. There are two general subjects at the core of those discussions; one is more focused on developing theories, conventions, common agreements, and projects between different countries. The other deals with the practical or real world experiences, which in some respects follow the outcomes of the theoretical approaches.

Almost parallel to the development of world heritage conventions and charters such as UNESCO and ICOMOS, Europe came up with their own recommendations and guidelines for underwater cultural heritage including Moss1, MACHU (Managing Cultural Heritage Underwater)2, and the Baltic Sea activities. Moss was set up with the aim of monitoring, safeguarding and visualizing shipwrecks. Example projects include the Darsser Cog, in Germany, the Burgzand Noord 10 wreck in the Netherlands, the E. Nordevall in Sweden, and the Vrouw Maria in Finland.

MACHU is a collaboration between Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and United Kingdom, which all are situated along the coastal maritime routes, and aims to share and discover more about the history of Europe and maritime development. The countries along the shores of the Baltic Sea -- Denmark, Finland, Latvia, Poland, Russian Federation, and Sweden -- also got together with the concept of "common sea, common culture3" to find more about the development of sea faring/sailing and culture and history.

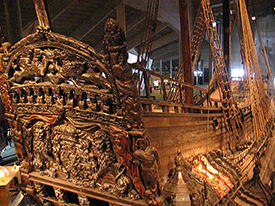

The decorated stern of the Vasa. Photo by permission of Creative Commons. (Large View)

Some of the more well known archaeological projects in Europe occurred in Denmark, Holland, France, Sweden, and England. I have divided the projects in two general categories; one I call the classical way of study which is excavation, transferring the finds out of water, conservation of removed materials, and their presentation in a museum for public display. The second category, influenced by pressure from the world heritage organization, limits destructive excavations as well as promotes non-physical excavation methods and in situ preservation and presentation. Hence, some countries are developing different methods of presentation according to their technical-scientific possibilities, climate, and natural issues. For instance in Denmark a mobile data presentation system is being developed for visitors who go to the actual wreck-sites where they will receive on-site information and complimentary data. What follows are some examples of projects in Europe.

The Vasa was one of the most intact shipwrecks in the world. It sank just a few hours after its first launching in 1628 due to technical problems in its construction. Transferring the vessel out of water, which at the moment is hardly acceptable according to the UNESCO convention, was an enormous effort. The conservation process took 17 years. A "glycol-method" was used which still raises some concerns about potential complications for this relic.4 The conserved vessel was put into a museum in 1990.

The Skuldelev viking boat. Photo by permission of Creative Commons.

One of the pioneer countries in underwater archaeology is Denmark with a large number of shipwrecks from the Viking period. The Skuldelev Ships project is important because from the start documentation, excavation, conservation and presentation to the public had been done simultaneously. Visitors were provided a platform to use for viewing the ongoing work.5 In 1997 the Viking Ship Museum, which exhibits the Skuldelev Ships from the Roskilde Fjord, added an exhibit called Museum Island, where visitors can see images of the original ships before having wrecked. The shipwrecks study provides an important key to understanding shipbuilding traditions and life in the past.

In the Maritime Museum of Bermerhaven- Deutsches Schiffahrtsmuseum- one of most intact and rarest cogs is on display. The Bremen cog6 was found in 1962 during an excavation for a new dock in Bremen, Germany. PEG - polyethylene glycol - was used to conserve the cog after removing it from the water and sand. After conservation the planks were reinstalled and put on display. The conservation and stabilization on this cog continues.

The Bremen Cog. Photo courtesy of the author. (Large View)

In situ preservation is a relatively new development in the conservation and presentation field. This approach could preserve links between the artifacts, their contexts and also their intangible and memorial values, and could open a new museology philosophy. In the case of in situ preservation and reburial there is little chance for presentation, but it safeguards and preserves for future research potential. This method consists of excavation, archaeological studying, reburial of objects in their original location or in some similar condition. Major concerns for this method include the environment and accessibility of the place.

The 1988 BZN 3 wreck7 in the Wadden Sea is one of the first in situ protection projects in the world. This in situ protection consisted of covering the site with sandbags and polypropylene nets. Throughout the years this method has been simplified and now only the nets are being used.8 Underwater preservation could be followed by underwater trails for diving visitors where the climate and nature of the water allows and also virtual presentation for some more difficult diving areas.

The other experiment in conserving and presenting the underwater shipwrecks is inside an aquarium which has been done in Sweden. The Aquarius method has a great potential for archaeological waterlogged wooden artefacts, whether the purpose is public display, storage before conservation, long-term preservation, or conservation. In wrecks that contain iron, problems occur that are strictly related to iron corrosion.9 This experiment could highlight the possibility of providing in-similar-situ condition for preservation and presentation of underwater relics and sites where the sites in their original locations are endangered.

Apart from shipwrecks there are some historic and prehistoric sites as well as sunken villages and cities in different parts of Europe like the village of Walraversijd in Belgium, the 16th century village of Fall in Germany, Sanguinet in France and so on. Limited research and studies have been done on some of them.

These projects highlight the importance of the context and natural environments and other issues involved in providing a sustainable future for the underwater historic sites in Europe. The practice of underwater archaeology is truly interdisciplinary, combining the methods of various fields of study including anthropology, chemistry, ethnography, geology, history, naval architecture, oceanography, and paleography during the time of excavation and study, and at the same time methods of preventive conservation, preservation and presentation should not be ignored in order to have a sustainable underwater cultural heritage.

Return to In The Field home page.

Footnotes:

1 http://www.nba.fi/Internat/MoSS/eng/index.html

2 http://www.machuproject.eu/index.html

3 www.baltic-heritage.net/reports/1st-cultural-heritage-forum.pdf

4 Ulrike Koschtial, The 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage: advantages and challenges, Museum International, No. 240 (Vol. 60, No. 4, 2008), UNESCO 2009

5 The excavation of the Skuldeve ships in 1962 generated considerable interest. About 30,000 people visited the site.

6 http://www.dsm.museum/MA/cog.pdf

7 http://www.nba.fi/Internat/MoSS/eng/bzn-10.html

8 NAS 2006 Conference Speakers, Martijn Manders, 25 September 2007.

9Preservation, storage and display of waterlogged wood and wrecks in an aquarium: "Project Aquarius", Bjordal CG, Nilsson T , Petterson R, Journal of Archaeological Sciences, 34 (7): 1169-1177 JUL 2007 .

Comments, suggestions, or questions can be directed to research@themua.org