May 4, 1851

Edward Mickle looked across the wharf at the advancing wall of smoke. Since late last evening, when the fire began, Mickle had nervously listened to the roar of the flames. The bright glow in the sky, the flying sparks and the hoarse shouts had seemed distant, but now, well into the new day, the wind shifted. With terrifying speed the flames raced across the waterfront. Fire licked beneath piling-supported floors, weakening and collapsing the still burning buildings into the shallows of the bay.

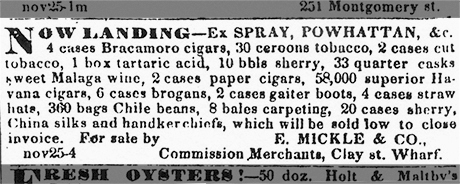

A typical advertisement for goods offered at auction by Mickle & Co., this one is for goods landed from the ships Spray and Powhattan, and appeared in the San Francisco Daily Alta California of November 25, 1850 (See More Ads).

One block west, along the Clay Street wharf, the ship Niantic began to smolder. Suddenly, explosively, the ship burst into flame. Embers thrown by the wind swept across the wharf and landed at Mickle's feet. "Get out the pump!" he shouted up to the crowd on the deck of the ship General Harrison. Mickle's fortune was invested in the ship now ringed by fire. Inside her hold lay tons of merchandise – imported wines and liquors, rolls of fabric, and fancy foods. As the frantic men pumped, fetid salt water from the tidal shallows washed over the thick oak planks of the hull

It was too late. The wind whipped sparks from the nearby Niantic onto the General Harrison, and the ship began to burn fiercely. Mickle and the men with him turned and ran. The inferno engulfed the waterfront. Workers chopped at the pilings of the wharves stretching out from the burning shoreline and toppled them into the bay. Their quick action cut off the advance of the flames, and saved hundreds of other ships that lay in thick clusters in the deeper waters of the city's anchorage. Standing on the truncated end of the Clay Street wharf, choking in the thick smoke, Mickle stared as General Harrison dissolved in a wall of flame.

The interior of General Harrison, showing the midships area of the hull, burned to the waterline, and exposed during excavation in September 2001. Photo by James Delgado (Large View).

September 10, 2001

Deep inside the excavation, the backhoe carefully pulls back the layers of sand. The last scrape of the huge bucket exposes a dark-stained layer. I put a hand up to stop the huge machine, and pick up the high-pressure hose. As the water washes over the area, sand streams away to expose a thick, dark layer of ash, burned wood, melted glass, and twisted metal. Tips of charred pilings become visible. They lie alongside the fire-scarred planks of the General Harrison. Archaeologists and construction workers had laboured over the last week to uncover the ship from her tomb of mud and sand.

With the General Harrison's half-burned hull exposed where she burned and sank on May 4, 1851, the excavation now turns to the area surrounding the ship. The General Harrison, we discover, is hemmed in by remnants of the fire that burned her down to her waterline.

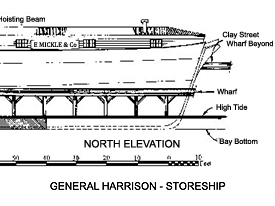

Architectural draftsman John W. McKay worked with the archaeological team to reconstruct the storeship General Harrison on paper (Full Plan).

The ship lies, today, several meters beneath the street level. Lining the construction fence on the streets above are hundreds of spectators drawn to the incongruous spectacle of a ship lying deep in the heart of San Francisco's Financial District. Behind them tower the steel and glass of high rises. Two blocks to the west, its spire half concealed by the fog, the Transamerica Pyramid marks the long-buried shoreline of the Gold Rush waterfront.

Watching the high-pressure hose strip away the shroud of mud and sand is like stepping back in time. The oak planks of the ship's hull are solid and the wood bright and fresh. Even more amazing is the stench of burned wood and sour wine rising from the charred debris. A century and a half ago mud, water and sand sealed the ship and burned wreckage so perfectly that time has stood still. The still fresh smell of the fire transports all of us standing in the excavation back in time to a long forgotten disaster at the beginnings of San Francisco's history.

Caught up in Gold Fever

Product of the venerable New England seafaring town of Newburyport, Massachusetts, the General Harrison commenced her career on April 28, 1840. Newburyport, over the previous century, had built many ships, including coastal schooners and small brigs. Now the town's shipwrights were turning their hands to more modern, larger merchant ships like the General Harrison. A full rigged, three-masted ship, Harrison was 126 feet long, and 26.7 feet wide. Inside her 13 and half-foot deep hold, the ship could carry up to 409 tons of cargo. She just couldn't carry cargoes out of Newburyport. The steady silting of the harbour entrance meant that large ships needed to clear port empty, and sail down to Boston or New York to load.

During her nine-year career as a "packet," General Harrison worked out of New York, running south to New Orleans with passengers and cargo, and returning north with southern cotton. She also worked out of Boston. Then, in 1849, news that gold had been discovered in California swept through the United States. The editors of the New York Herald remarked in early January that the "spirit of emigration which is carrying off thousands to California…increases and expands every day. All classes of our citizens seem to be under the influence of this extraordinary mania….Poets, philosophers, lawyers, brokers, bankers, merchants, farmers, clergymen – all are feeling the impulse and are preparing to go and dig for gold and swell the number of adventurers to the new El Dorado." Most chose to go by ship, and between December 1848 and December 1849, 762 vessels sailed from American ports for San Francisco.

One of them was the General Harrison. Sailing from Boston on August 3, 1849, the ship rounded Cape Horn in a seven-month voyage that ended on February 3, 1850 in San Francisco Bay. With her passengers off to the gold fields, and her cargo sold, the General Harrison would have been ready for another voyage. But the lure of gold was too much for her crew. They deserted and headed for the mines. The General Harrison, along with hundreds of other ships, lay idle on the San Francisco waterfront.

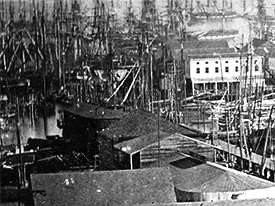

General Harrison and the neighboring storeship Niantic are visible in this waterfront view of San Francisco taken in December 1850 (Large View).

Despite the presence of that "forest of masts," the waterfront was then a constantly growing, hectic center of activity. Every day, more ships arrived, workers landed cargoes, and thousands of men crowded the sandy streets seeking passage up the bay and its tributaries to the heart of the gold country. Crowded beyond its capacity, San Francisco was boxed in on all sides by massive, shifting sand dunes and a shallow cove that was either a stagnant pond or a sea of thick, foul mud at low tide.

San Francisco entrepreneurs solved the problem by subdividing the shallows of the cove and building on them. Unsold cargoes, garbage, and sand thrown into the bay helped fill in the shoreline. Pilings driven by the thousands, shipped south from the forests of British Columbia and Puget Sound, allowed long wharves to march across the mud flats to the anchorage. Alongside the wharves, buildings perched atop piles, and ships hauled in and stuck in the mud served the needs of the booming frontier town.

By the time of the General Harrison's arrival, a Chilean visitor to San Francisco described it as,

A Venice built of pine instead of marble. It is a city of ships, piers, and tides. Large ships with railings, a good distance from the shore, served as residences, stores, and restaurants. I saw places where the tide had flowed down the street, turning the interior of houses into lakes. The whole central part of the city swayed noticeably because it was built on piles the size of ship's masts driven down into the mud.

The frequent fires that ravaged the city exacerbated San Francisco's need for buildings. After one particularly bad fire, in May 1850, the mercantile firm of E. Mickle & Co. purchased the General Harrison to serve as a "storeship," or floating warehouse. Workers removed the ship's masts and hauled her up onto the mudflats alongside the Clay Street wharf. Just a block west lay the storeship Niantic, beached in August 1849 and a survivor of the last fire. Nestled in the mud, her hull still washed by the tide, General Harrison was quickly converted into a warehouse. A large "barn" was built on the deck, doors cut into the hull, and the hold cleaned out to accept crates, barrels, and boxes of merchandise. Mickle & Co. advertised, on May 30, 1850, that "this fine and commodious vessel being now permanently stationed at the corner of Clay and Battery streets" (then just marks on a surveyor's chart) was "in readiness to receive stores of any description, and offers a rare inducement to holders of goods. Terms exceedingly moderate and the proprietors are determined to afford every satisfaction to those friends who may avail of the facilities presented."

The "fine and commodious" facilities were available for only a year. Just before midnight, May 3, 1851, San Francisco again caught fire. Whipped by the wind, the fire spread throughout the city. Engulfing whole streets, the flames crumbled supposedly "fire proof" brick buildings and swept under the wharves. On May 5, weary San Franciscans looked out over a barren landscape of charred pilings and half fallen brick walls. More than 2,000 buildings were gone, including the storeships Niantic, Apollo, and General Harrison. To rebuild their city, San Franciscans hauled sand down from the surrounding hills and covered over the burned area.

The reminiscences of one pioneer reported that workers uncovered the remains of the General Harrison around 1857. Charles Hare, a "ship breaker" who worked with San Francisco's Chinese community, reportedly "broke up" the old ship and hauled off her remains "piecemeal," along with dozens of other Gold Rush ships left on the waterfront. After that, the story of the General Harrison gradually faded from memory.

Return to In The Field home page.

Comments, suggestions, or questions can be directed to research@themua.org

Additional information related to this topic by Dr. Delgado can be found here:

Gold Rush Port

The Maritime Archaeology of San Francisco's Waterfront