Research central at a campground near Mackinaw City, MI (Tent camping idea credit Ben Ford)

Recently I took two weeks off from my duties as Director of the MUA to conduct my second research trip for my dissertation on the British maritime cultural landscape of the western Great Lakes in the late eighteenth century. My goal for this trip was threefold. First, I needed to conduct archival research to find and read fur trader journals, account books, ships’ logs, and letters to and from General Thomas Gage, who commanded British Forces in North America after 1763. The second goal was to visit the colonial fortifications that were so important to British maritime efforts during this period, such as Fort Michilimackinac in northern Michigan, and Fort St. Joseph on St. Joseph Island, Ontario in northern Lake Huron. I wished to visit these sites because they’ve been active in archaeological research for decades. Their reports and publications would surely contribute to my understanding of their maritime history. My third goal was to physically visit the environment in which the various historical actors lived, traveled, traded, and died. I firmly believe one should visit those places in order to understand as much as possible about the relationship between the landscape and history.

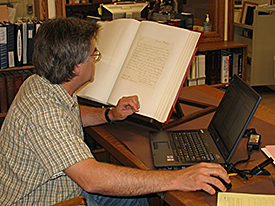

Reading a letter to General Gage from 1771 at William L Clements Library.

The majority of my first week was spent at the William L Clements Library reading the Gage Papers. The staff was incredibly helpful and the opportunity to talk to curator Brian Dunnigan, one of the most knowledgeable historians on the colonial Great Lakes, was invaluable. After an initial run through on how to request materials I settled down into a routine that took me through hundreds of letters encompassing various aspects of life on the British Great Lakes. I blessed the souls of those individuals, long since passed, who had neat handwriting and struggled to make sense of those with a script worse than my own. Many of the letters were fascinating, covering such topics as how to treat local Indians, complaints about how bateaux men occasionally drained the brine out of barrels of pork to lighten the load (resulting in rancid provisions for the troops), and how best to keep a particular young officer from trying to get too cozy with his commanding officer’s wife.

Each day at ten o’clock a staff member would ring a hand bell thus announcing tea time where researchers could have tea or coffee with the staff. My first reaction was to keep working but I went for coffee instead. I strongly recommend to anyone who gets the opportunity to take advantage of the chance to get to know the staff and your fellow researchers. While at the Clements library I happened to meet Dr. Keith Widder, a former historian at Fort Michilimackinac, whose book on the fort during the American revolution is on my reading list for the summer. Dr. Widder was conducting research for his next book and was so excited to share what he was working on as well as to hear about my research that we talked for an hour. Dr. Widder generously shared tips on additional sources I might not otherwise have found. During one of the coffee breaks a volunteer sitting next to me suggested I go with him up to the exhibit area - a room that I didn’t originally plan to visit. When I did I was rewarded with the opportunity to see the famous painting The Death of Wolfe by Benjamin West, which depicts British General Wolfe’s death at the Battle of Quebec during the French and Indian War. West painted this scene five times. His largest version hung before me. I couldn’t get over the feeling of collegiality that pervaded the folks working not only just at the Clements but at all the libraries and archives I visited during this trip.

Archaeological research at Fort Michilimackinac.

After a week of eavesdropping on General Gage’s conversations I headed north to visit Fort Michilimackinac, where I had made an appointment with registrar Brian Jaeschke to spend some time in their research library to review their collection of archaeological reports, dating as far back as 1959. Fort Michilimackinac is located on the south shore of the straits of Mackinac where lakes Michigan and Huron come together, and is also close to the St. Mary’s River portage to Lake Superior. It was a central meeting place for Indians and fur traders in the region. Settled by the French in the early eighteenth century and surrendered to the British in the French and Indian War, the post had a long European merchant and military occupation period, to say nothing of the thousands of years of native encampments. With close to a million artifacts recovered and analyzed, Fort Michilimackinac must be one of the most thoroughly studied colonial fortifications in North America. The library’s book shelves were full of both published and unpublished reports. Brian kindly introduced me to Dr. Lynn Evans who currently directs the archaeology at the fort. Dr. Evans was gracious enough to take time out from the dig to answer my questions. Her publications, including a paper on the use of Native American technology in the fur trade as well the other reports produced at the fort, will add key information that might not otherwise be available in archival documents.

Throughout my research I’ve paid special attention to comments by contemporary writers related to the impact of the environment on the British Empire. The third goal for my trip involved viewing that environment first hand. For instance, during the first part of this trip I drove along the Canadian side of the Detroit River. I had read an eyewitness account about how Indians involved in the siege of Detroit in 1763 thought they might have a chance of attacking schooners from encampments on islands in the river. While this seemed improbable to me in theory even after looking at historic maps, seeing the narrow channels first hand gave me an appreciation for why they thought their plan might work (swivel guns and muskets ensured it didn’t).

A sign that perhaps I'm not in Virginia anymore.

Hoping to obtain similar insights, I departed Fort Michilimackinac and took a day trip headed north into Canada. I visited Fort St. Joseph located on St. Joseph Island. Fran Robb, who works at the park, and I had been in email contact for almost a year so it was good to meet her face to face. Her love of the national historic site was obvious as we toured the stone ruins of this large fur trade and military complex from the late eighteenth century. The British relocated to the island after turning over their post on Mackinac Island to the Americans in 1796. It was not only a military establishment but was also a major fur trade center and housed offices for the British Indian Department. While several stone foundations have been excavated and are presented to the public Fran pointed out that numerous buildings lay hidden in the underbrush yet to be excavated. The island sits in the St. Mary’s River and despite the cloudy skies I could make out the numerous islands surrounding this strategic location.

We headed down a path that led to the beach where the army landed their bateaux when bringing in supplies. The constant stream of complaints I’d read in contemporary letters about the short lives of bateaux made sense when I saw the conditions along the beach. Baseball and softball size cobbles make up much of the shoreline providing a punishing environment for the small wooden craft. One example of a bateaux, discovered underwater in the 1960s, was raised and placed on display at the visitor’s center. The thin wood and light construction made it easy to see why replacement bateaux were in constant demand.

At the end of two weeks I reluctantly turned my car south and headed home from the lakes region. I had much to think about as the three data types played over in my mind: archival, archaeological, and environmental. I had gathered numerous pages from books, articles, letters, maps, and journals that I would begin reading when I arrived home. Unfortunately my car broke down 150 miles from home. It’s never a good sign when a mechanic’s first words are, “how much money do you got?” That set back was a minor one when tallied against all the positive aspects of the trip. I’d gotten a taste of the camaraderie amongst those who are out there dedicated to preserving and researching the past either in the archive or the test unit. I had a chance to see misty clouds roll through the islands in a remote region of Lake Huron, so remote in fact that one could easily imagine fleets of birch bark canoes making their way across the small bay or bateaux ferrying provisions from sloops and schooners anchored far out in deeper water. I arrived home ever more convinced that researchers must spend time in the environments in which their stories took place, that historians need to avail themselves of the relevant archaeological reports in order to tap into the three dimensional archive. Mostly I came home convinced that I am very fortunate to be able to spend time in the company of so many good folks out there willing to assist a fellow time traveler on his road trip to the eighteenth century.

Sites visited during this trip:

Fort Malden, Amherstburg, Ontario

William L Clements Library Ann Arbor, Michigan

Detroit Public Library’s Burton Historical Collection

Fort Michilimackinac, Michigan

Fort St. Joseph, St. Joseph Island, Ontario

Return to In The Field home page.

Comments, suggestions, or questions can be directed to research@themua.org